I have contended in this webbook (Chapter 10, Why It Matters) that hell, still pervasive in our religious thought today, causes significant harm. If we think that God abhors sinners and will one day give up on them, casting them into a place of eternal conscious torment, then their value diminishes in our eyes and it is easy for us to despise them.

Think about what kind of hate must have been in the hearts of the artists featured in this gallery. Look at each piece of art closely. What do we see? Read the commentary on each and decide for yourself. Is this a healthy view of people that may not see things as we do?

Welcome to the Gallery of the Hell Myth. Please remember – none of what you are seeing is biblical, none of it is true. It has all been conjured up in hearts full of hate.

From The 11 Most Nightmarish Depictions of Hell in Art History by Alexxa Gotthardt for Artsy.net. The commentary on each is her’s. This gallery spotlights the development of depictions of Hell through art driven by imagination, not scripture. Go to Article

Working in the Netherlands over 100 years after Giotto, the pioneering oil painter Jan van Eyck created his own Last Judgment scene on the right half of a diptych that also includes a depiction of the Crucifixion. While measuring only about 22 by 7 inches, the Last Judgment panel packs a bone-chilling punch thanks to Van Eyck’s garish depiction of hell, which Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Maryan W. Ainsworth has described as a “diabolical invention.”

Beneath the outstretched arms of a giant and menacing skeleton tumbles a cascade of damned souls, each subjected to a different form of punishment. In one corner, a man screams in pain as he’s disemboweled by a serpent. Elsewhere, a demon—part skull, part sharp-toothed jaguar—gnaws on a fleshy rump. The anguish here is so evocative that Ainsworth has characterized the scene as cacophonous—viewers can almost hear the sounds of torture: “The cracking and breaking of bones, the gnashing of teeth of the monsters relentless in their pursuit.”

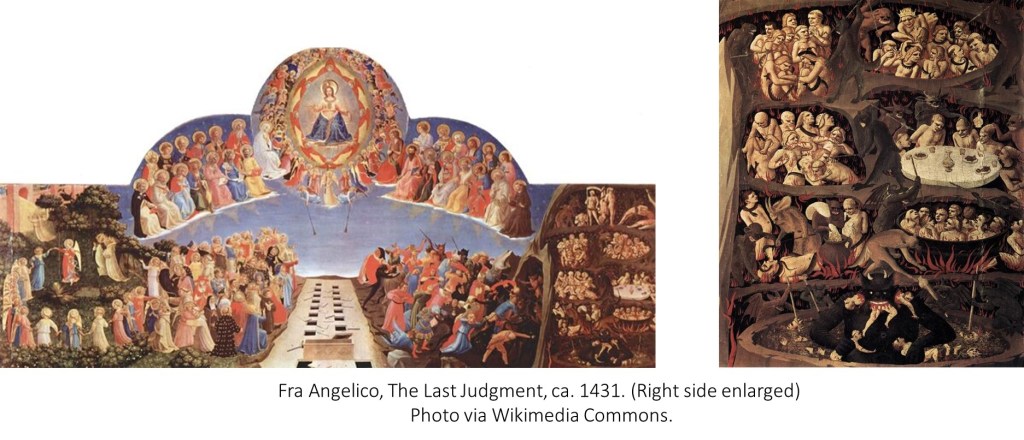

Posthumously nicknamed the “Angelic Painter” by his acolytes, the Dominican friar Fra Angelico—known as Fra Giovanni during his lifetime—is somewhat ironically renowned for several of his visceral hellscapes. Perhaps his most horrifying scene comes from a fresco depicting the Last Judgment, originally created for the basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Rome (it now hangs in Florence’s Museo di San Marco).

Here, the artist takes a cue from Dante, visualizing hell as a tenebrous cave where the damned are grouped by their sins; each of them has its own tailored brand of torture. For instance, those guilty of greed have melted gold coins poured down their throats, while those guilty of wrath are forced to incessantly fight each other. At the base of the fiery pit, Lucifer chomps on human bodies as he simultaneously bathes in a soup of melting souls, dutifully stirred by a cohort of demons.

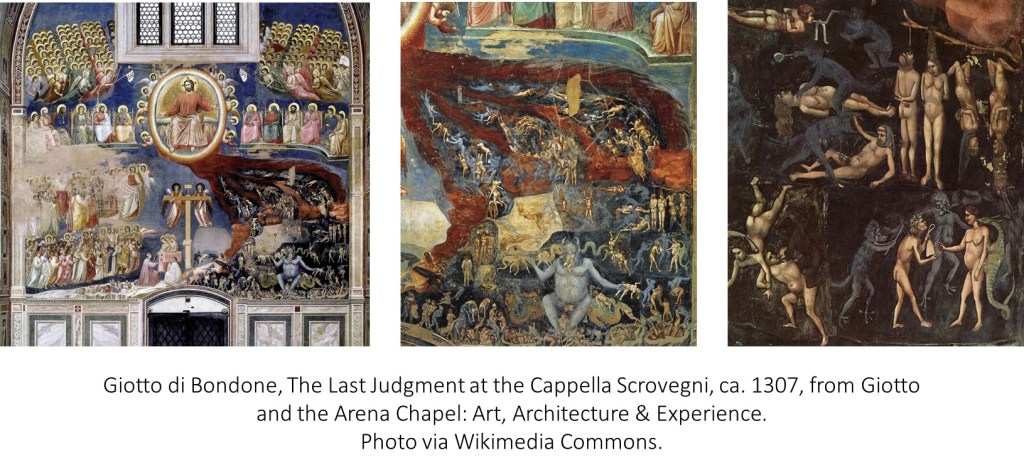

Florentine painter Giotto had a flair for the dramatic. Like most artists working at the dawn of the 14th century, he primarily painted frescoes for the private chapels of wealthy families. Yet his paintings are utterly unique: The Biblical characters that fill his compositions aren’t flat and stylized like those of his Byzantine forebears. Instead, they writhe with red-blooded energy and fierce human emotion.

In the lower right-hand corner of the fresco, a gluttonous, horned monster (likely Satan) stands at the gates of hell, devouring sinners, then unceremoniously excreting them. Such cruel and unusual punishments abound: Naked men and women are dragged down to hell by fearsome black demons, where they are spit-roasted and speared or stuffed into deep pits. Dante himself likely visited the fresco as Giotto painted it; according to historian Giorgio Vasari, the two were “dear friends.” Dante began writing his Divine Comedy around the time Giotto was painting the Arena Chapel.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. At the back of the chapel lies one of art history’s most impressive paintings of the Last Judgment, the momentous event described in the New Testament when, at the end of the world, God either shepherds the dead to heaven or banishes them to the fiery underworld. The religious text doesn’t leave many clues as to what hell might look like, so Giotto built on past artistic interpretations, as well as his own fertile imagination.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder also had a knack for shocking his audience. “Like a director of horror films, the painter tried to appeal to all the senses in order to arouse fear and create pleasure at the same time,” Bruegel biographer Leen Huet has written. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his 1561 canvas Dulle Griet (Mad Meg), which takes a cue from Bosch and explores hell through the lens of contemporary Flemish culture.

This painting depicts the folkloric character of Dulle Griet, the leader of an all-female army on a quest to pillage hell. Her strength is underlined by her massive scale; she dwarfs both her compatriots and her opponents, a multitude of fantastical demons that dot the otherwise familiar Dutch landscape. Bruegel has depicted the underworld as an eerie fusion of fantasy and reality. Griet seems to run toward a literal gaping “mouth of hell,” its scaly skin resembling bricks in the surrounding architecture. Instead of devouring the dead, the monsters of this hell battle flesh-and-blood warriors.

Some scholars have also read the painting as an exploration of 16th-century Netherlandish gender dynamics. A 1568 book of proverbs provides context: “One woman makes a din, two women a lot of trouble, three an annual market, four a quarrel, five an army, and against six the Devil himself has no weapon.” In this way, the painting can be read as a study of female power. Is Griet a greedy agent of chaos or a heroic victor who isn’t afraid to go head-to-head with the Devil?

There can’t be a discussion of hellscapes without Hieronymus Bosch, whose spellbinding masterwork The Garden of Earthly Delights rivals the fame of Dante’s Inferno. The Dutch painter came of age in the mid-1400s during the Protestant Reformation, when Christians began to interpret the word of God for themselves, rather than rely on the Church as an intermediary. Bosch incorporated this approach in his painting, depicting heaven and hell through rollicking, chaotic scenes set against a contemporary Dutch backdrop.

Rather than the fiery pits mentioned in the Bible or explored in depth in Inferno, Bosch shows hell as a raucous battlefield teeming with horrifying, surrealistic creatures who take pleasure in torturing their human opponents. The painting’s fame may be largely due to the proliferation of mesmerizingly odd details: A dismembered foot hangs like a prize from the helmet of a spiny bird-monster; other sinners are stretched taut across giant instruments and played by beady-eyed demons, or eaten and then pooped out by their aggressors.

Pandemonium, the Capital City of Hell. (Le Pandemonium, John Martin, 1841. Louvre.)

The Pandemonium (1841) goes back to a passage in the first book of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, in which “Pandemonium, the palace of Satan, rises suddenly built out of the deep.” In a diagonal perspective characteristic of Martin, a gigantic building complex extends along the waterfront. Martin’s Satan, whose invocatory figure stands on a rocky outcrop in the right foreground, has the look of an ancient Greek hero. Like Achilles outside Troy, he appears with shield and feathered helmet, but commanding an army not of besiegers but of demons and damned souls in their Cyclopean city.

Both Dante’ and Milton depict Satan as the ruler of the underworld as though he is waiting there now for the unrighteous dead as they expire to be cast into his dark realm. These poets portray the angels that fell from their first estate as demons devouring and torturing sinners as they arrive in the 9th circle of hell.

This couldn’t be farther from the truth. Satan is not now or ever will he be the ruler of Pandemonium, or anything else in the lake of fire and his demons will not dine on the flesh of sinners, they won’t torture or torment them. This is all a lie – every bit of it!